“War for the Planet of the Apes” comes to theaters this weekend, and I have not been so excited and nervous about a movie since the first “Lord of the Rings” film was released in 2001.

This recent iteration of the Planet of the Apes series is the most spectacular sci-fi series of the last 20 years. But in addition to being wonderful films, they are a showcase for the winner of most important behind-the-scenes technical power struggle since the emergence of digital effects: Andy Serkis, who plays Caesar, the main character in the Apes films.

As this clip demonstrates, Serkis isn’t the “model” for Caesar, he is Caesar. The technology of motion capture allows Serkis to “wear” the digital character as if it were an impossibly perfect costume, to own the character completely and have every nuance of his performance shine through into the end result.

The ability to do this with an actor’s performance is not something that happened overnight, nor something that was inevitable. It is the latest triumph in Serkis’ long career of advocating for the importance of the actor’s role in creating digital characters. Because of this, though he is certainly not the most famous actor of our time, Serkis is the most important actor in movies in the last 15 years. His work has changed the trajectory of digital characters and established the primacy of human passion, individualism, and artistic intent at a pivotal moment when it could all have run off the rails.

But to understand this, you have to go back through the history of the digital character.

The Threat of Photorealism

Back in 2001, actors were getting nervous.

Computer graphics were moving past characters like Jar Jar Binks and into much more photorealistic characters. Robert Zemeckis (director of Forrest Gump) was starting to make digital scans of all the actors in his movies (you know … just in case) and the “Final Fantasy” movie was showcasing how digital actors could almost look real.

This was “photorealism” 15 years ago. Stop laughing. We took it very seriously.

This was “photorealism” 15 years ago. Stop laughing. We took it very seriously.

Visual effects coordinators were making ominous claims about the capabilities of CGI characters and how they could supposedly eliminate human actors . Claims like “computer graphic actors … don’t do any complaining” must have sounded good to movie executives, but threatened to remove the artistic contribution of the actor from the creation of the digital character.

Then Andy Serkis changed history.

Gollum and the Gamble Within a Gamble

It seems like a foregone conclusion that the Lord of the Rings films would be blockbusters, but the series was a terrifying gamble. In an age before Marvel’s never-ending-movie-series-cinematic-universe, Jackson was an unknown director working on a three-film series with a visual effects crew made up largely of people who volunteered by yelling “oh, pick me! I want to make Gandalf” instead of using the premiere visual effects powerhouse that was Industrial Light and Magic (George Lucas’ visual effects company).

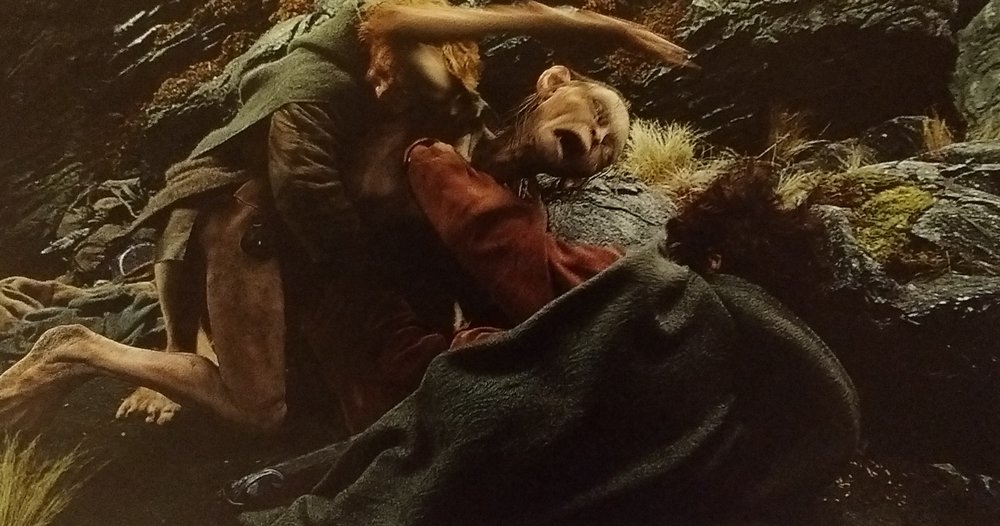

The character Gollum posed a unique challenge. Emaciated, deformed, and twisted by thousands of years of suffering, Gollum was a character that no amount of prosthetics or make-up could bring to life. He would need to be fully digital.

Gollum was an absolutely pivotal character to the story, a character of conflict, anger and sorrow. He had to be perfect, a CGI character who could convince the audience that he lived in this world; a solid, raw, physical character capable of both internal emotion and physical menace. The challenge was so monumental, they ultimately decided to punt on him for the first movie, showing only glimpses of Gollum at a distance and in the shadows.

Luckily for the audience (and the movie industry as a whole), they cast Serkis into the role.

Pause for a moment to keep in mind that, at this time in filmmaking history, when a digital character was in play the actor was expected to provide the voice and perhaps some motion capture data for physicality. The majority of the character work was usually done by animators after the fact.

Indeed, for the Hulk character in Ang Lee’s 2003 Hulk film (in production at ILM during the same time Serkis was playing Gollum), they didn’t even use Eric Bana’s face for the Hulk character. Instead, they modeled it after Lee’s young son’s juvenile expressions of rage. The prevailing concept at the time was that digital characters were the responsibility of the technologists, animators, and rendering artists. An actor could provide some grounding, but the character “belonged” to the digital artists, not the actors. It would be considered perfectly acceptable to have one actor provide the voice, another the body motions, and have the animators handle the facial expressions on their own.

But through his performance as Gollum, Andy Serkis demolished that theory.

The first step came during the shooting of the live action scenes. Serkis was on set for every Gollum scene, acting the part out along with Frodo (Elijah Wood) and Sam (Sean Astin). The idea was to digitally “paint” him out later and replace him with a computer generated Gollum. To this end, Serkis wore a tight “gimp” suit that would keep the edges of his person clean and sharp, making it easier on the effects team to remove & replace him in post-production.

But something funny happened. Serkis could have played it safe, knowing he would be replaced later on anyway. Instead, he brought a ferocity to a performance that everyone thought would simply be abandoned. In fact, it was so powerful a physical presence that the digital artists working on the Gollum character lamented the fact that he wore a mask. They wanted a clearer view of his face so that they could more easily replicate his in-the-moment performance for Gollum.

This was a pivotal moment for visual effects and the creation of digital characters. Serkis argued strongly in favor of the actor “owning” the performance and collaborating with the digital character artists after the fact to help bring the character to life. This was a seismic shift in the paradigm of how to create a virtual character.

In his next major digital performance as King Kong, Serkis worked closely with the effects team to develop motion capture rigs and prosthetics that allowed him to lose himself in the character.

This is no small feat.

Placing an actor in a motion capture studio runs the risk of isolating them from the environment of the film. The more technology you surround them with, the harder it gets to deliver a performance. Serkis was a pioneer in developing motion capture technology that allows the actor to focus on the character and deliver a compelling performance.

Arm extension prosthetics allowed Serkis to “play” King Kong, providing facial expressions and physical motion capture for the giant ape character.

There is always a risk with the limitations of motion capture that the actors will find it difficult to focus and engage the drama if the technology is obtrusive or overwhelming. If your digital character performance is the responsibility of the actor, the actor needs to be able to perform with minimal intrusion.

Serkis was the godfather of this approach and worked with both digital artists and motion capture experts to develop ways of allowing the actor the freedom to perform while capturing that performance in enough detail that it could be translated into the final computer generated result.

Which brings us to the Planet of the Apes series.

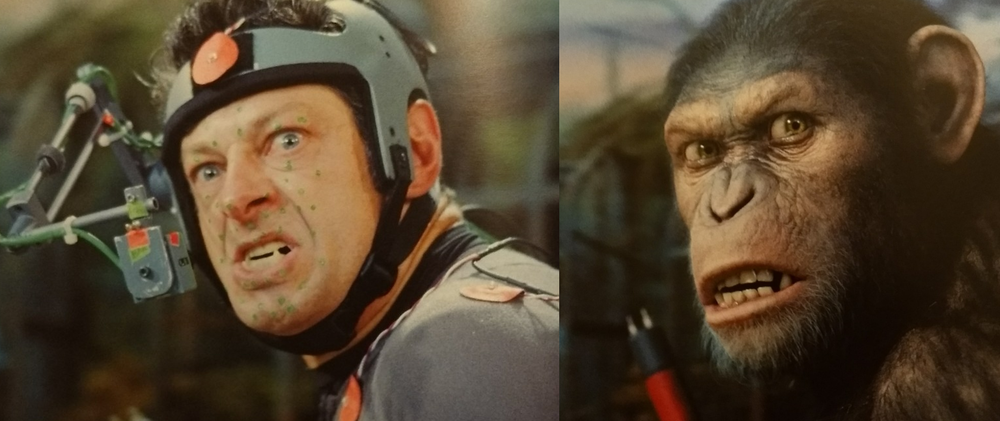

The arm in front of Serkis’ face is a camera to closely capture his facial performance. You can see the dental prosthetic he used to get into character and help his face make more ape-like expressions.

The arm in front of Serkis’ face is a camera to closely capture his facial performance. You can see the dental prosthetic he used to get into character and help his face make more ape-like expressions.

One of the big complaints about “Rise of the Planet of the Apes” was that the simian characters seemed more compelling than the human characters. This seemed an odd complaint since it was the core dramatic point of the story. The main character certainly isn’t Will (James Franco), it’s Caesar (Andy Serkis). The fact that people felt a little put off that Caesar stole the show and drove the story is the ultimate triumph for Serkis’ decade-long work in trying to make actors the auteurs in charge of the digital characters. The whole thrust of the movie was that the apes were more human than the humans were.

“Rise of the Planet of the Apes” had several other ape characters that relied on other actors truly owning their digital performances. These rich characters were vital in “Rise” because we had to buy that Caesar could be the leader of a community of apes. Developing a community necessitated a group of actors working in the techniques Serkis used to sell his own performances as Gollum and King Kong. This meant training the actors to work within the constraints necessary for a digital performance and teaching them to communicate to the digital artists when they felt a particular nuance of the performance wasn’t being represented in the final result.

“On location” performance capture is not easy. But the question in character performance capture in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes is “Do you want it done easy? Or done right?”

“On location” performance capture is not easy. But the question in character performance capture in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes is “Do you want it done easy? Or done right?”

If “Rise” was a trial for creating a cast of actor-driven digital characters, “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes” was the real test. “Dawn” focused heavily on the civilization that the apes had developed and, as such, relied on the ape cast to come across as distinct both in visual style and personality. Caesar is determined but compassionate, Koba is conniving and vengeful, Maurice is wise and protective. These traits come across in the character visual design, but that alone would never have been enough to secure audience interest and empathy. It is the performance that sells the character.

If performance sells the character, then the character rightly belongs to the actor. Andy Serkis demonstrated this in action and has spent years convincing and demonstrating that this is the truth of compelling digital characters. They draw their reality, their humanity, from the actors who create them, not the computers that render them.

I’ve not yet seen “War for the Planet of the Apes,” so I can’t say for certain that it is a continuation of Serkis’ amazing work. But in a certain way, it doesn’t matter. The real war was for the souls of the digital characters we will be watching for the next 50 years. That’s the war Serkis was fighting and the war he won by proving through his own tenacious example that actors provided a core to these characters that couldn’t be abstracted out and replaced with a computer.

Some are calling on the Academy to recognize Serkis’ role as Caesar in consideration for an Oscar. My own terrible opinion is that it doesn’t matter. Oscars come and go, and people forget Best Pictures that are forgettable.

Remember “The Artist”? Of course you don’t, because it wasn’t a memorable film.

Serkis has already won something far more important than an Oscar. He’s won the artistic and philosophic battle of how we should connect to cinematic characters that aren’t real. At a moment when digital characters threatened the humanity of cinema, Serkis reminded us that passion and emotion, anger and sorrow, all the things that make us human, are not things that can be created by a computer. Serkis convinced an industry that it’s the actors who lend their souls to the characters they create. We should all be grateful to him for that.

We’ll never be able to drag an “anger” emotion plug-in onto a digital model and make it angry in the way that an actor can be angry. We’ll never bring genuine sadness that doesn’t come from the well of human experience an actor brings to the scene. Relief, joy, fear … these are all things we can teach a machine to recognize as artificial intelligence advances. But only an actor can bring us into the moment.

Back in 2001, the promoters of purely digital characters thought they had the system for creating digital actors figured out. “Once you sit down in front of that box,” said one effects supervisor, “It’s infinity in there. Given enough time you can make that box do anything.”

Serkis proved they were wrong. The box can’t generate a soul.