The last month I’ve spent most of my evenings and weekends putting things in boxes as I prepare for a move across the country. Between fighting to get my kids back in school and being so far away from the rest of my family, it’s time to make the change that I’ve been slowly contemplating for years.

I have a friend who is also moving this summer to be closer to his family. We’ve talked about what pushed us into these decisions and he is convinced that, even while lockdowns brought schools and businesses to a standstill, the pandemic has accelerated the decision making for many people and forced many hands. Some hands have been forced into making a positive change, like making a move to be near family, or getting married, or finally giving that ultimatum at work.

For many small businesses, the hands that were forced were losing hands. I hold the very firm belief that every person has a story and that especially goes for small business owners. Every struggling business has its own story, its own heartbreak, its key players, pitfalls, shocking revelations, personal dramas. These are stories worth telling.

As I sort all the objects of my life and pack them into boxes, I packing up every issue of Cinefex, a long-running journal of visual effects. I’ve been a Cinefex subscriber for many years and have always looked forward to discovering the next issue tucked in my mailbox, granting me an insiders view of the visual effects industry. Unfortunately, with the crush of the pandemic and the collapse of theaters, Cinefex sent out their final issue a few months ago.

Nothing lasts forever, but I always wish the good things lasted just a little bit longer. Saying goodbye to Cinefex, I felt like it was appropriate to give a eulogy. I want to suffer the loss by remembering the best things.

The first issue of Cinefex was March 1980 and featured articles covering Star Trek – The Motion Picture and Alien, both articles written by founder Don Shay. These articles went far beyond a typical magazine spread of glossy photos and chirpy quotes associated with movie marketing.

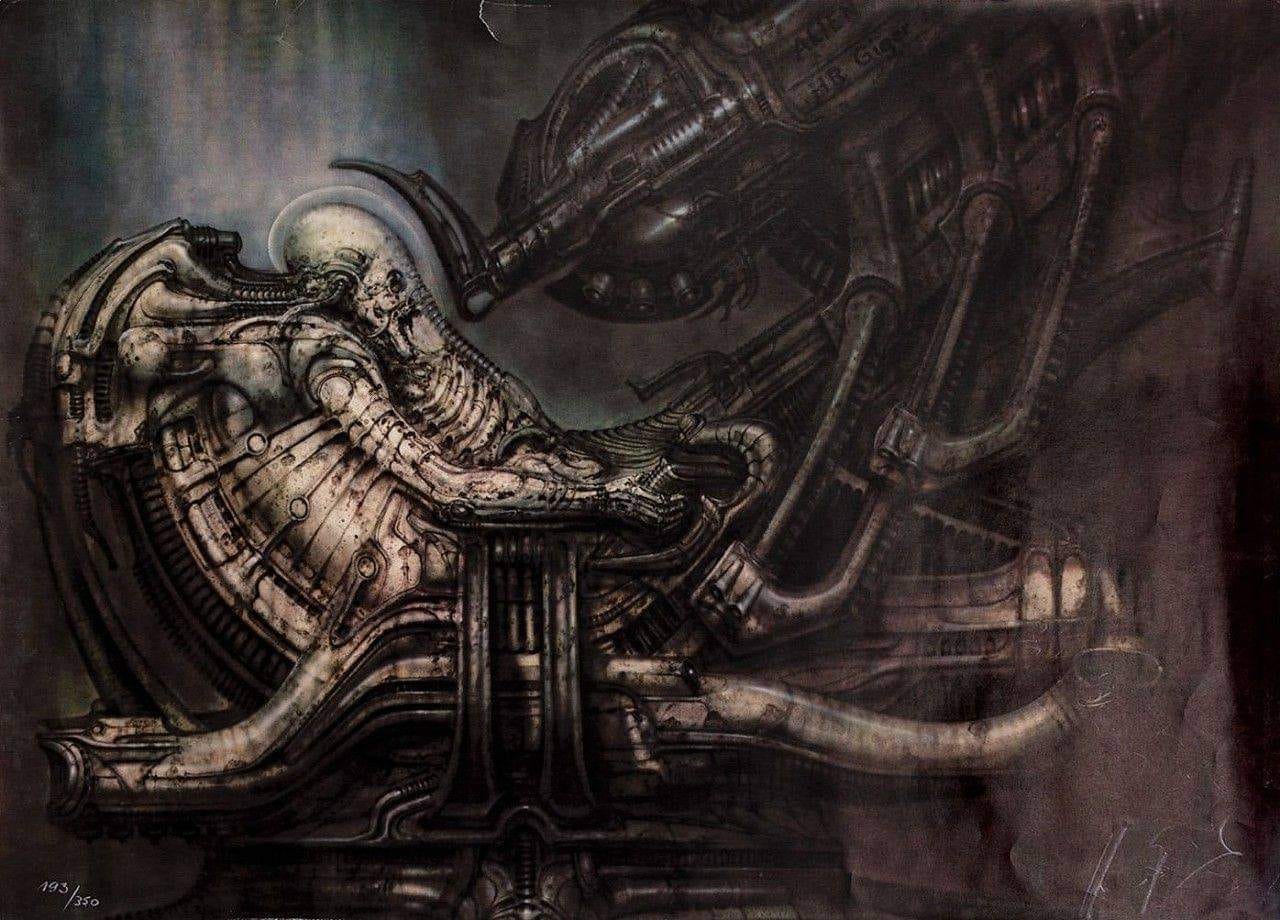

In the Alien piece, Shay writes for several pages about the process of designing the xenomorph (alien) creature in all its stages. He covers how they recruited HR Giger, a surrealist painter whose aesthetic was an innovative form of static biomechanical terror, into providing the bulk of the aesthetic, from the spacecraft design to the body of the “space jockey”, to the xenomorph, both larval and fully grown.

It would have been the simplest thing in the world to simply walk through the film shot by shot and give a dry description of the “how” of these visual effects, but Shay was not content to give only technical details. He wanted to communicate the complex blend of artistic vision, large-scale problem solving, experimentation, technical tinkering, and financial tug-of-war that goes into developing visual effects that really bring a movie to life.

To this end, we get the story of how Ridley Scott went out of his way to recruit Giger and how Scott had to pitch to the studio to increase their budget. There’s the story of how Giger had been burned by film-makers in an abandoned Dune adaptation and became increasingly involved with Alien as he discovered that they really did want to bring his designs to life.

We also get the tiny technical details that reveal what a labor of love looks like. For the chest-bursting scene, Scott had a very specific vision of how the creature would emerge and reveal itself. He wanted it to first puncture Kane’s chest, but not his shirt, as blood exploded across the room splattering the horrified crew. After two unsuccessful attempts at its own birth, the xenomorph would burst through chest and shirt to greet the world.

Shay provides pages of details about how this scene was made, both the technical obstacles to bring it to fruition and the choice to keep the actors in the dark about what exactly what was going to happen. For the first take of this scene, Scott didn’t even film the effect; he wanted to capture the actors’ genuine shock and horror as blood and viscera sprayed across the room.

To capture the precise and escalating terror of the scene, the nature of the shirt tear was an important component to Scott, so the effects crew had to experiment with weakening the shirt fabric with battery acid so that it was strong enough to stretch and dome up on the first few violent punches, but tear asunder when the creature finally emerges.

But what made Cinefex so wonderful was to read about the hard work that went into making these movies and then to watch the scene for yourself and appreciate the precision, the care, the money, and the technical work that goes into 3 or 4 seconds of a quality visual effect.

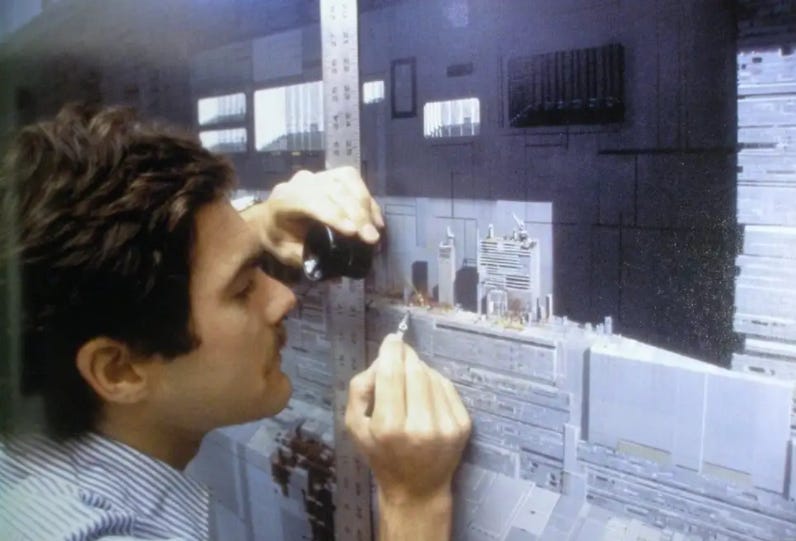

The genius of Cinefex was to make that connection between the intent of the artist and the hard work of creating the images. They were showing us the backlot and we could see the miniatures and watch as the filmmakers made the hard choices between what they had in their minds and what was technically and financially feasible. On occasion, Cinefex would even show us the moment when a scene or shot wasn’t working and the director and effects designers would be forced into another strategy. These weren’t hagiographic everyone-is-a-genius promotional pieces. These were about the vision, hard work, and compromise that is necessary to pull off a compelling visual that supports and enhances the underlying story.

Cinefex came of age in the 80’s, a golden age for practical visual effects and creature design. In an age before digital compositing (stitching multiple filmed elements together using software), visual effects were primarily created “in-camera” which meant visual effects directors needed to be familiar with an array of strategies for creating illusions of scale without building cities worth of sets and costumes. Vast landscapes were often achieved through matting, a process of layering a portion of the film frame so that moving models or live-action components could be seen against a highly detailed static background.

The practice of visual effects became a menagerie of arts that encompassed painting, makeup, sculpture, modeling, robotics, material design, engineered camera work, and compositing multiple elements together for the final image. Some visual effects artists dove deep into a specific component of their field while others preferred a role that was more akin to tinkering and problem-solving.

When computer graphics started making their debut in films, Cinefex was right there, putting Tron on the front cover of issue 8 and writing about the innovation that digital graphic could bring to the movies. In contrast to the snub that the Academy Awards gave to Tron (refusing to even nominate it for visual effects because using computers was considered “cheating”), Cinefex took the yeoman’s approach that this was just another way to put fantastical images into a movie and the story of this new approach was a story worth telling.

In the decade that followed, every new issue seemed to cover some exciting development in visual effects. At first, computer graphics were so expensive that shots requiring CGI had to be chosen judiciously. But through the 90’s, computers became more affordable and the practice of digital visual effects became an industry unto itself. The 90’s brought audiences stunning advances in visual effect wrapped in blockbuster films like Terminator 2, Jurassic Park, Titanic, and The Matrix. All these films utilized digital effects with practical effects to create some of the most iconic cinema of the decade.

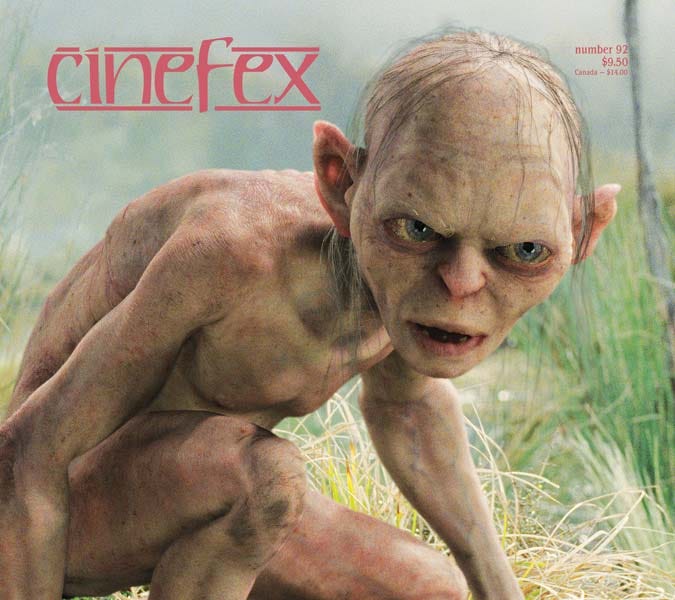

This is when I came to discover Cinefex, at the very center of the publication’s life. I was a teenager, obsessed with the upcoming Lord of the Rings films, anxious that they find success and eager to know how they planned to pull off some seemingly unfilmable sequences involving hobbits that live among Big Men, structures too large to build, battles with warriors too numerous to cast and costume, and a peculiar creature who was absolutely central to the story but was so emaciated and other-worldly that he would have to be a fully digital character.

The visual effects story of the Lord of the Rings films is far too long to detail here. While the films themselves were lauded and recognized both commercially and critically, it is not widely understood what a landmark of visual effects these films represent.

Many of the most convincing hobbit shots were filmed using a technique called “forced perspective” which (to my delight) is basically just the use of mathematics and optical illusion to shoot an entire scene in which one person seems miniature and another full grown without any digital compositing at all. This technique had been used for many years in film, but the Lord of the Rings films used high-precision technology to allow them to shoot forced perspective shots even when the camera was moving.

Each of the challenges that were evident were tackled with an unending energy and clear passion from the crew. Those structures that were too big to build became miniatures the size of buildings, dubbed “bigatures”. The unfilmable battles of thousands were a made a reality through Massive crowd simulation system, a software project developed by Stephen Regelous specifically for use in The Lord of the Rings and worthy of its own book on how a unique and massive technical advancement can be achieved by a tiny team through hard work and desperate need.

And Gollum, the purely digital creature who needed to stand as his own character in a live-action film? Not only was that technical challenge met, but Andy Serkis used this opportunity to start a dialogue between actors and visual effects artists that ended up driving the very history of how we approach digital characters.

If you’re interested in the fight over the artistic ownership of digital characters, I wrote about it a few years ago in a piece that was deeply informed by (you guessed it) Cinefex and their articles detailing that struggle for the artistic integrity of digital performances over two decades. It’s such a deeply important tribute to humanity and artistic expression and it’s a story that would be known to only a few people within the industry were it not for Cinefex.

The Lord of the Rings films were a once-in-a-generation advancement in visual effects. They blended the old world of practical effects, modeling, and makeup with the emerging world of digital wizardry that could deliver previously impossible illusions to bring a world of fantasy to life. All of this was lovingly recorded in my beloved Cinefex.

In the years after the triumph of the Lord of the Rings films, there was a slow but discernable change. There was a movement in the world of visual effects to do more and more things digitally. As this inclination advanced, the Cinefex articles sometimes became difficult to follow. There were articles that became largely a recounting of the difficulties of managing a digital render pipeline or the struggles of rendering scenes at an IMAX resolution. It’s not that these things are unimportant, they are essential to the practice of digital image generation. But these struggles become removed from the artistic trial and error, from tinkering and creative innovation.

This is not to say there was no innovation in the field. Advances were being made constantly to deliver astounding images and impossible visions. The Curious Case of Benjamin Button implemented an astonishing advancement in performance captire to become the first film in which a largely digital performance was nominated for an Oscar. Similarly, Avatar was an enormously successful and innovative visual effects production that created fantastical characters and impossible visuals.

But the Cinefex articles for many films felt increasingly rote. As movie makers came to believe that anything was possible in a world of digital imagery, they came to view visual effects artists less as artists and more as technicians. Where once a surrealist artist would collaborate with the modeling and effects team to produce a film with a unique production aesthetic, now visual effects companies were being given storyboards by callous producers and told to make them a reality with no concern for practical reality.

A tendency that breaks my heart is when people with talent and passion who love to build things allow people who wish to profit off their passion to work them to death. Video games is an industry where we often see this. Visual effects is another. Passionate technical people love to make things. We want to make beautiful things, things that make people smile or laugh or stand in awe. Only as we grow older and more jaded do we realize that we need to set a gate to our passion and talent.

As visual effects became an increasingly digital practice, there came a tendency to push effects houses to produce more for less. Major effects houses began to feel the pinch as studios played visual effects houses against each other, pushing for more and better and offering status and bragging rights as a substitute for money. Desperate to be included in the latest and greatest in visual arts and worried lest some upstart under-bid them, visual effects companies bent to these ruthless markets.

Things eventually came to a head when Bill Westenhofer, having just won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for The Life of Pi tried to highlight the unsustainable nature of a visual effects industry by pointing out that the firm that just won an Academy Award had been forced to declare bankruptcy due to unpaid bills and unreasonable studio demands.

This was a truism across the industry. Studios increasingly demanded high output from visual effects houses without recognizing the underlying financial and artistic realities of the medium. They would leverage the prestige of high-name directors or tease the possibility of long-term deals on multi-film properties (cough Marvel cough) only to shift to a younger low-cost competitor at the drop of a hat. This cycle of behavior became an industry practice. Studios would work with an effects house at skeleton wages until that house finally demanded just compensation for their high-quality work. At that point the studio would shift to a younger, more naïve effects house that was unfamiliar with this pattern of betrayed promises.

For Cinefex, this didn’t just mean less interesting stories to tell. It meant a studio system that simply didn’t want anyone telling the stories.

Despite my seemingly anti-journalism persona, I really believe that the role of the journalist is an essential one because it is ultimately the role of a story-teller. As a denizen of a post-modern world, I recognize the impossibility of an impartial narrator, but I still think the most important job of the journalist is that of a historian who exists in the now. They (we!) have a responsibility to tell the stories around us as they happen, with joy and energy, as cleanly and kindly and accurately as possible.

My genuine belief in the importance of these stories is what made me a devotee of Cinefex in the first place. And it is why my heart broke with issue 143. In issue 143, the Cinefex team sent a writer to cover Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation. That article included the following (truncated) preface:

We at Cinefex have always prided ourselves on presenting our readers with the very best in visual effects journalism… In recent years procuring that imagery has become increasingly problematic, due to a proliferation of approval authorities at the studio, production and talent levels, all empowered to kill an image for whatever reason. Or no reason.

What we were provided (for Rogue Nation) were stock presskit images, including non-effects movie-star shots, artfully fakes still composites, and a few digitally falsified “behind the scenes” photos. After countless requests for reconsideration by us and by others on our behalf, we were forced at last to admit defeat – for the first time in our 35 year history.

To their credit, the Cinefex team published a wonderful article about the effects of MI: Rogue Nation. But it was clear that the dam had broken. The artists were no longer in charge of the production. The suits had taken over and would fight tooth and nail against any discussion or love of the craft that could possibly reveal anything other than a sanitized, pre-packaged, marketing approved Instagram version of the world of movie making.

The bureaucracy of reserved idiots who have more power than talent were winning against the passion, intelligence, and curiosity of artists and technicians.

That was 5 years ago.

Since then, there has been some truly wonderful pieces. Blade Runner 2049 was a masterpiece of visual effects and I’m glad we have that account. Premiere episodic television like Game of Thrones, The Boys, and The Mandalorian set high expectations for production value while demanding production cost restrictions that made compromise a necessity. The stories of these productions harkened back to the earlier days of visual effects when compromise was an inevitable part of the game to be played.

But as the pandemic hit the in 2020, high-production cinema collapsed. Films slated for 2020 were pushed out to 2021. The studios that continued to make movies found that the pandemic was an excellent reason to bar non-essential personnel (like Cinefex writers) from the set. Faced with a dearth of content and commitments to a subscriber base, Cinefex made the painful but necessary choice and closed their doors, sending out their final issue February 2021.

I’m still devastated. For many years, I eagerly anticipated the next Cinefex to arrive in the mail. Even when the articles were about half-assed productions or poorly thought-out effects, I enjoyed the writing. I liked feeling like an insider, I liked hearing from voices from within the industry. I felt a kinship with these nerds and artists who worked so hard to make something beautiful and, with the death of Cinefex, the tie between us has been severed.

What remains is akin to the detritus we might see floating in the wake of a shipwreck. I was glad to see that Cinefex writer Graham Edward’s Illusion Almanac is soldiering on, having just published a piece on Godzilla vs Kong, a movie I loved for pure delight and spectacle.

![The Illusion Almanac: Creating Godzilla vs Kong by [Graham Edwards] The Illusion Almanac: Creating Godzilla vs Kong by [Graham Edwards]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1cbf67a7-5319-4f86-bc40-502f4b27bc2b_313x500.jpeg)

If I could make something exist by the sheer force of my longing and passion, I would bring Cinefex back to life in an instant. Instead, I’m packing up my Cinefex collection and remembering the astounding history of visual effects that they gave us and how the world is a richer place because of them.